Article Main Body

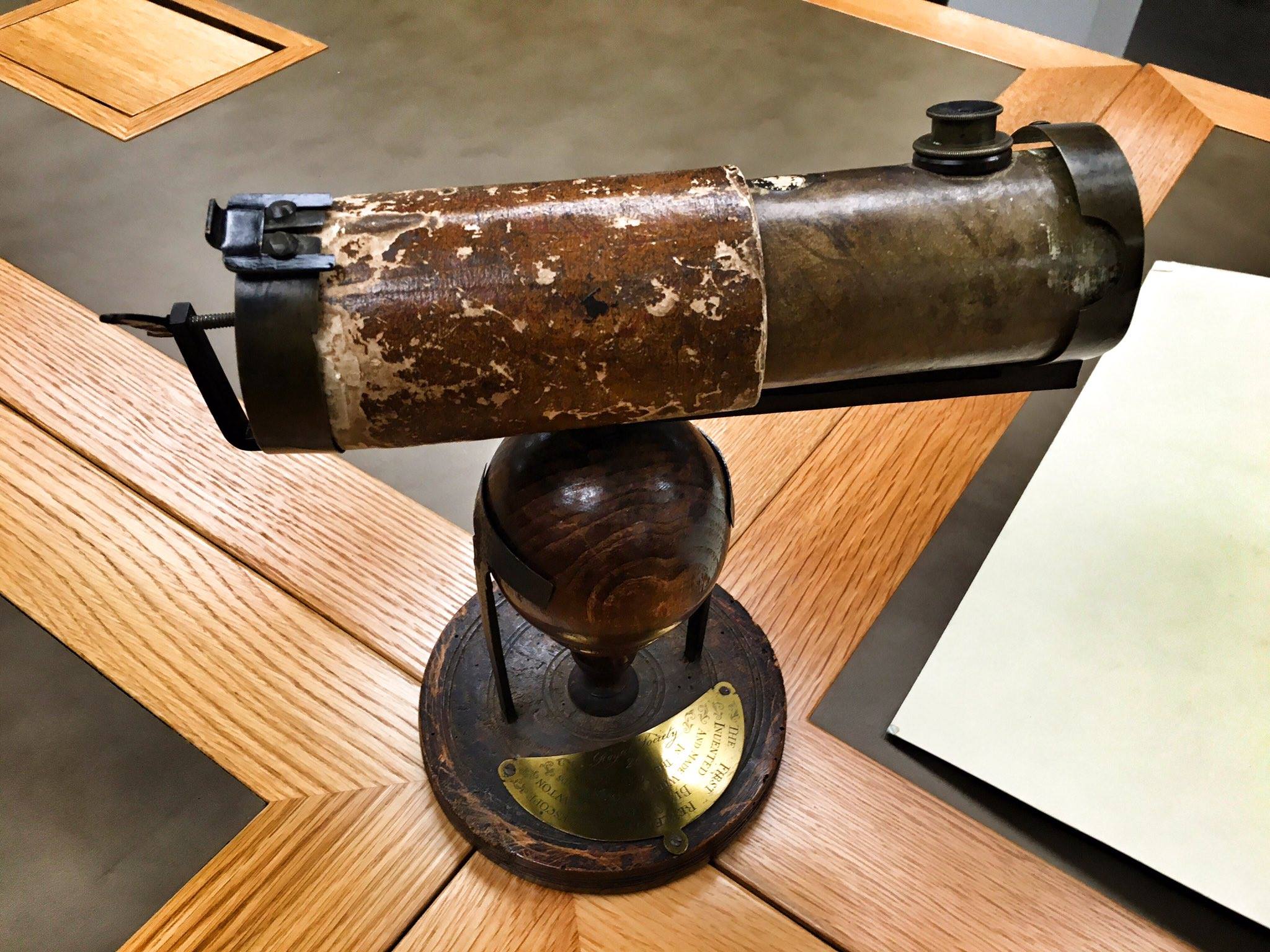

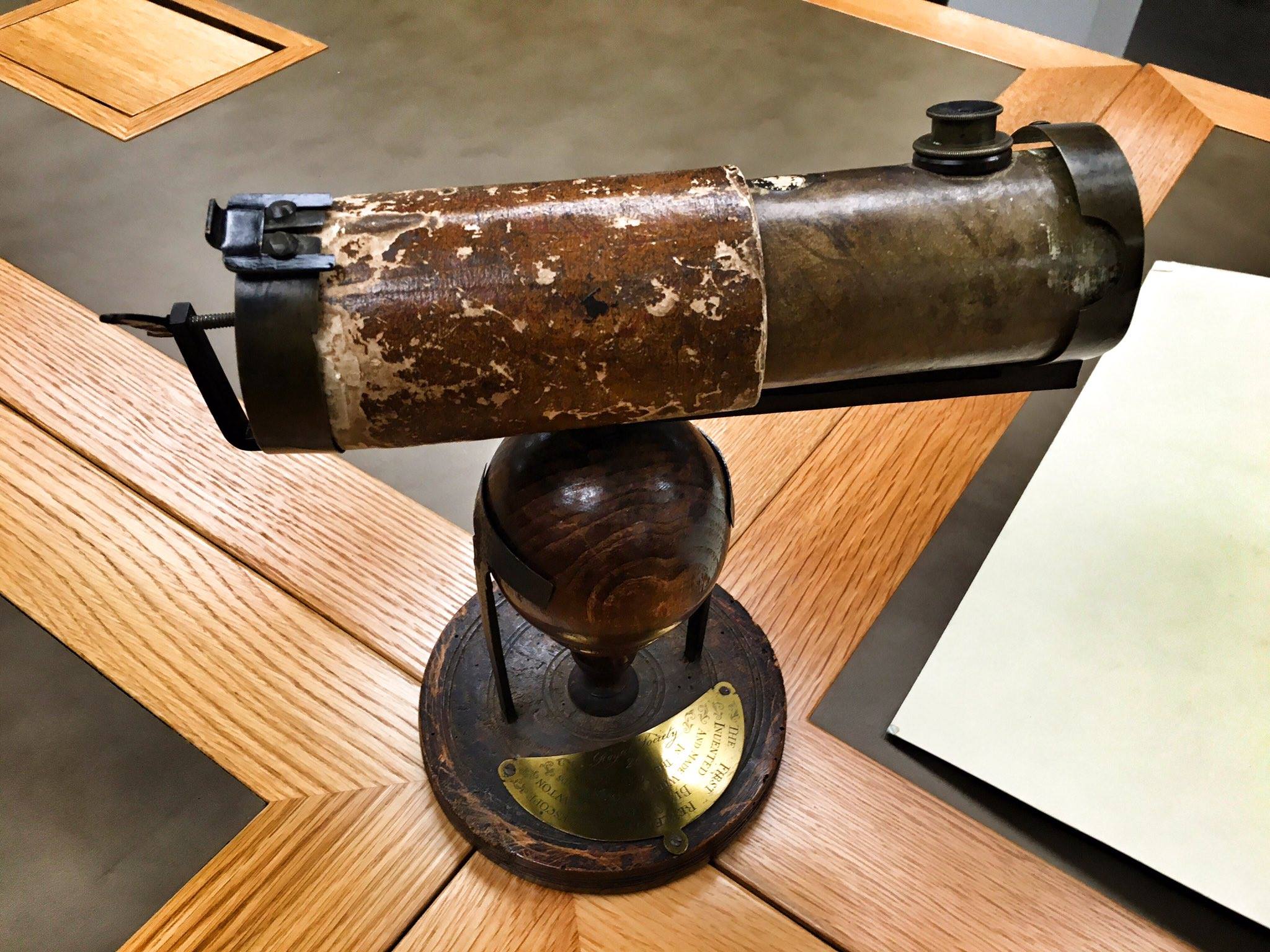

Figure 2: Newton's Telescope preserved at the Royal Society

Image Credit: Credits: Prof Alan Fitzsimmons

Many solar system researchers met at the Meteoroids 2016 (organised under IAU Commission F1) at ESA/ESTEC, Noordwijk and Cometary Science After Rosetta Meeting 2016 at the Royal Society, London, both held in Jun 2016. The author was one of the participants.

Comets have always fascinated scientists as well as the general public since time immemorial. Once upon a time, comets were considered as ‘carriers of bad omen’ and hence special interest went into studying and predicting their arrival in ancient civilisations. There are various references in history related to rituals and ceremonies conducted by old civilisations (evidence found in Mayan records by archae-astronomers was discussed in this conference too) in conjunction with appearances of comets and meteor showers.

After the invention of telescopes, it was possible to observe these objects with better clarity and find reasonably accurate astrometric positions so that their orbital details could be gathered. These orbital parameters, compiled from repeated observations, enabled scientists to predict the past and future of cometary orbits using Newton’s equations of motion and various other standard techniques in celestial mechanics.

Inspite of the outstanding contributions and wealth of knowledge acquired from the ‘formative’ comet era extending from Halley to Whipple, our studies about these bodies restricted to measurements from

a large distance (using telescopes). But cometary science has matured drastically since then.

In 1986, European Space Agency’s (ESA) Giotto mission had a close flyby to comet 1P/Halley during its most recent journey near the sun. This was a significant step ahead of all the previous ground based telescope observations of comets.

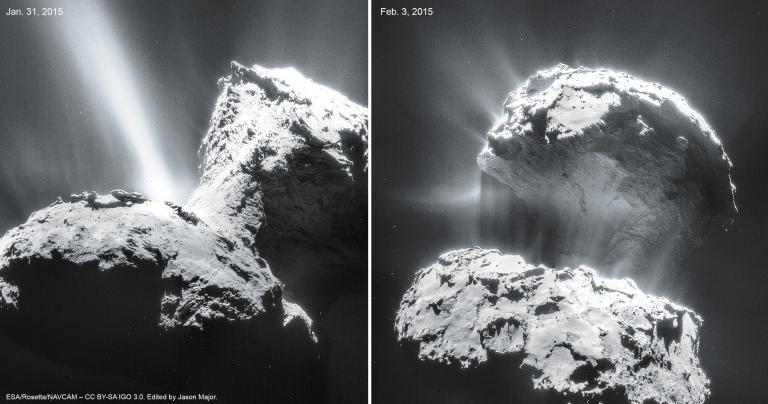

The studies on comets took an unprecedented new level in 2014 by the successful ESA’s Rosetta mission sending a lander Philae on to the surface of a comet. The final chosen destination for this mission was the comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko. Interestingly the time of submission of this article coincides with the last day of the Rosetta's tryst with 67P! :(

During both these conferences, there were various interesting ideas regarding the formation, structure and future of 67P, which has earned the nickname as a ’rubber duck comet’. There were multiple schools of thoughts regarding two or more separate pieces of material clumping together to form the ‘rubber duck shape’ which we see clearly from observations (see figure 1). Few scientists speculate the comet fragmenting into two due to the strong outgassing at the ‘neck’ feature and leading it to become a binary comet system in future. Because 67P is rocky and icy at the same time, there were interesting

debates about the boundaries between the classification of asteroids and comets. Because there are new asteroids which are being found comet-like (i.e. actively outgassing or ejecting material) and new comets being found which are asteroid-like (i.e. rocky or metallic), most of the community tend to agree that there is an asteroid-comet continuum in our solar system rather than two discrete populations strictly separated from each other (as previously thought).

Few discussions focused on the unique sungrazing cometary population which come dangerously close to the sun such that some of them get either fragmented (due to tidal forces from the sun) or evaporate (due to solar heat) or fall into the sun (due to near sun colliding orbits by Kozai mechanism). Interesting theories were presented about the formation, influx and long term dynamical evolution of Jupiter family

(orbital period upto 20 years) and Halley-type comets (orbital period from 20 to 200 years) from their source regions like the Kuiper belt and the Oort cloud.

In connection to the bigger picture, new results were presented by different scientists regarding the impact risks on Earth from different small body populations like fireballs, bolides, asteroids and comets.

The latest calibrated frequency vs impactor size estimates were presented and discussed using observational records compiled over last couple of decades.

For the safety of future space and satellite missions and to prevent them from high velocity meteoroid impacts, new approaches of modelling of dust trails in the neighbourhood of spacecraft was envisaged. For a short animation (developed by Dr Rachel Soja, Institute of Space Systems, University of Stuttgart) of the dynamical evolution of ejected dust trails from comet 67P (i.e. Rosetta mission target), check the

video: http://www.aanda.org/articles/aa/olm/2015/11/aa26184-15/aa26184-15.html

Both these conferences generated a good scientific and social overlap between the theoreticians, professional observers, amateur observers and space educators. Although scientists generally tend to disagree (peacefully?!) with each other about most things in life, on a lighter note, I think everyone jointly agreed on the famous Levy’s quote: “comets are like cats; they have tails, and they do precisely what they want!" :)

Blog

Blog